"Künstliche Intelligenz" or “Artificial Intelligence”? The Perception of German Language-based AI Research

Research data bites 13.

Key takeaway

Research outputs featuring “künstliche Intelligenz” cater to a specific, language-oriented use case on AI research for the native German language needs, mostly in outreach, teaching, and education.

Relevance to basic research, based on the scientometric data, is very limited on a global scale.

Artificial Intelligence dominates the discourse in today's Anglophone world, but its German equivalent, “künstliche Intelligenz”, is equally pervasive across German media, society, and politics. Surprisingly, the phrase also surfaces in research publications in a German context. Considering English is the lingua franca of science I'm very surprised that there is research published in German on AI using “künstliche Intelligenz” as the subject phrase of choice. Hence two questions arise: (1) Why would anyone publish in German when they know only German speakers can read them? (2) Is research on “künstliche Intelligenz” as prominent or as influential as its English-language counterpart? Does the disciplinary focus differ beyond information technology?

For this analysis, I treat the two phrases as interchangeable terms. In both searches, I limited the affiliation to include at least one German-speaking country-based affiliation (DACH; including Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Liechtenstein). Using the Dimensions scholarly database, I retrieved publications where either the term “Künstliche Intelligenz” or “Artificial Intelligence” appears in the title or abstract, deliberately excluding abbreviations (KI and AI, respectively) to avoid unrelated results.

Comparing Output Volume

Limiting the time period of interest to start with the year 2000 onwards the query reveals 3,738 publications containing “künstliche Intelligenz” versus 23,984 publications with “Artificial Intelligence” (see Table 1). The basic numbers indicate a noticeable use of the German phrase for “KI” in DACH co-authored publications, however counting the number of publishing outlets reveals a more limited breadth of 231 journals in the case of “KI” versus 3,769 different journals for “AI”. This shows a more limited number, but higher frequency of publication per journal (16.2 “KI” publications per journal versus 6.64 per journal for “AI”) and indicates the language bias of “KI” publications being more prominent in German-language-based outlets. With respect to other, citation-based metrics reflecting academic impact and beyond (patent and policy document citation) the German-based publications publishing on “AI” have higher numbers than German-based publications containing “KI”.

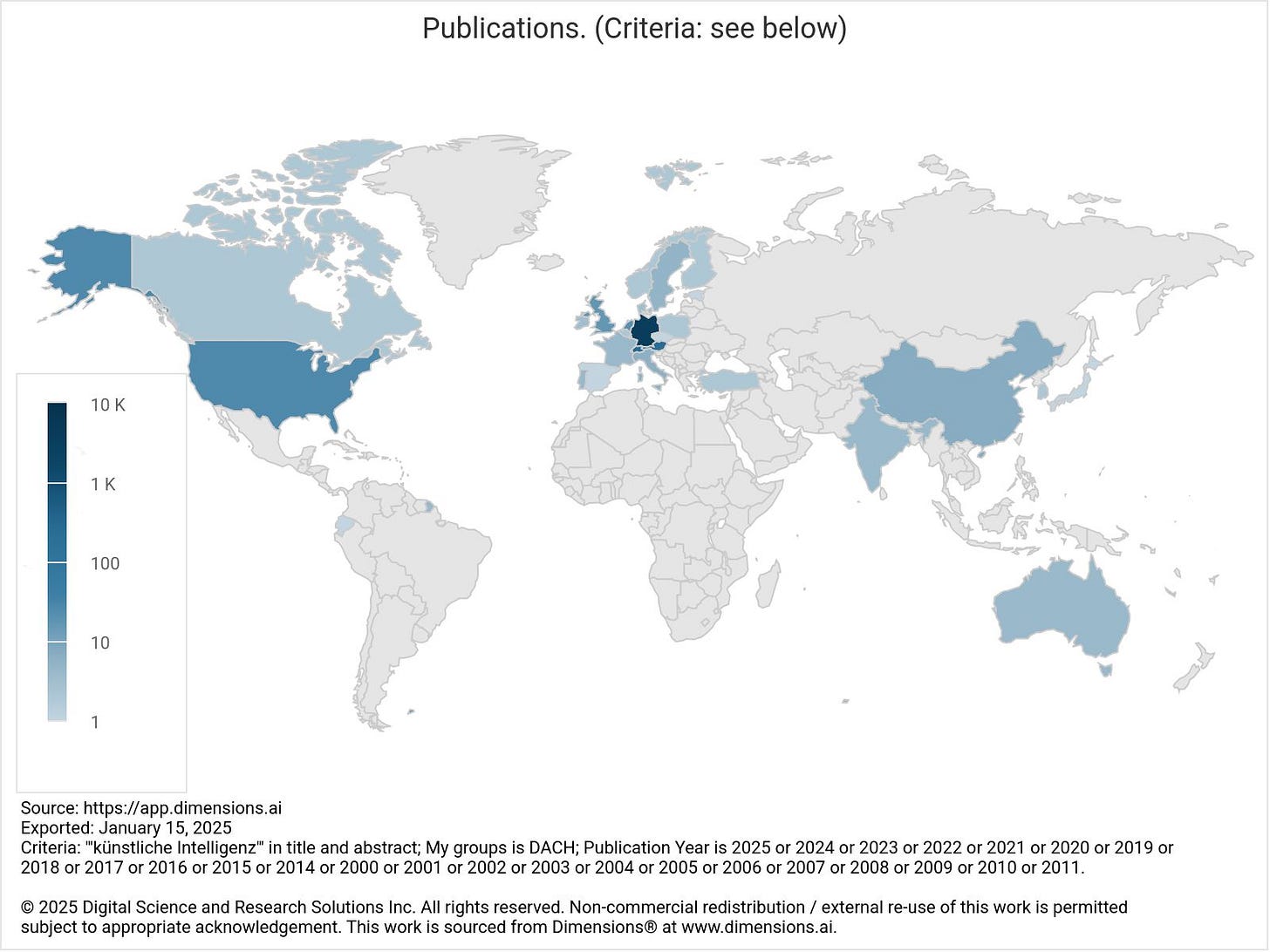

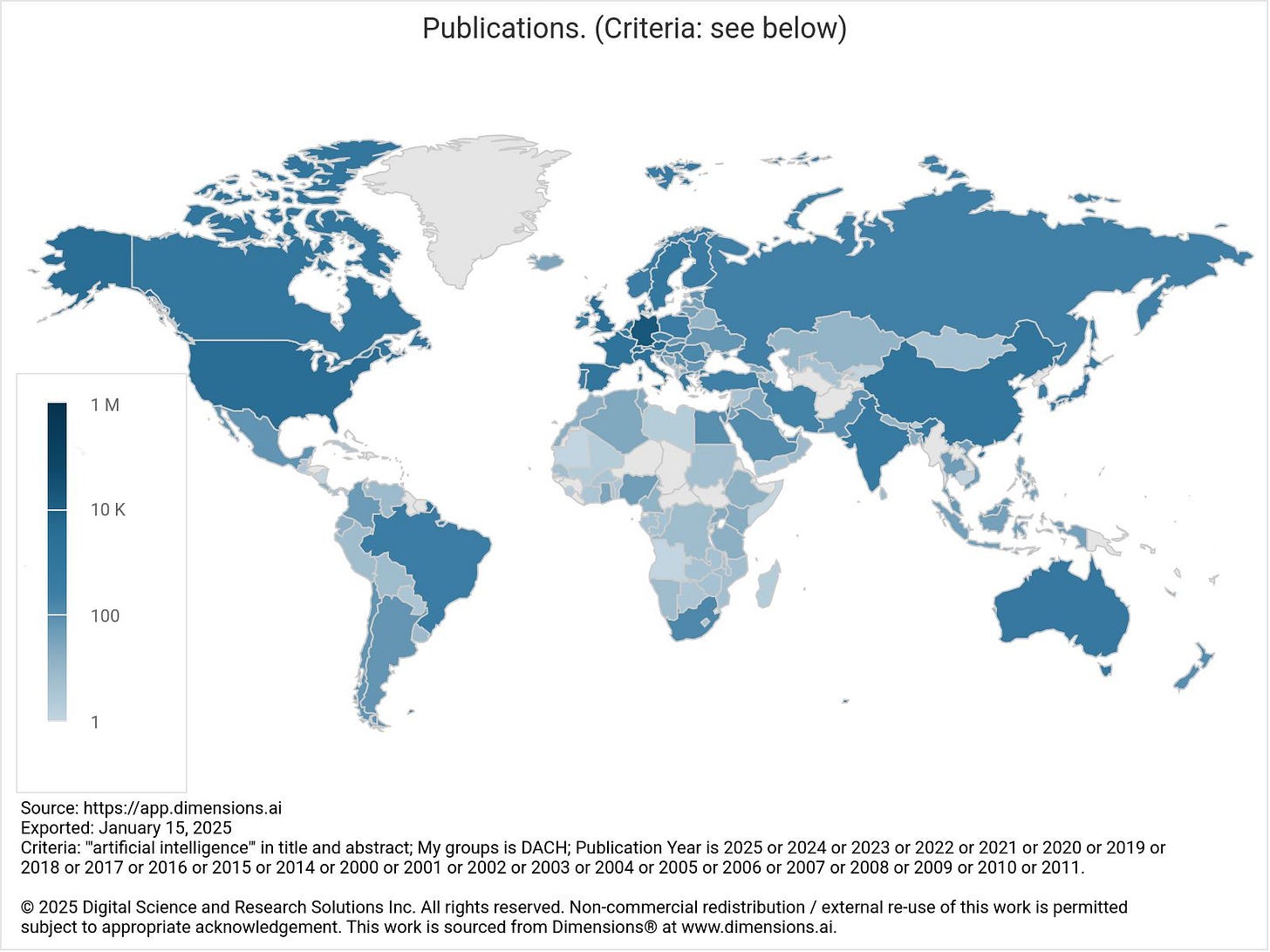

Geographic Spread

Without diving deeper into the collaboration patterns of DACH co-authored publications with AI or KI, the visualisation of the geographic spread of collaboration for the resulting papers is shown in the following geomaps (source: Dimensions). Whilst DACH collaboration containing “AI” is globally distributed and strong in numbers, the DACH collaboration on “KI” publications is heavily focussed on DACH only with few internationally co-authored publications.

Impact, Citation Trends, and Disciplinary Shifts of “Künstliche Intelligenz” vs “Artificial Intelligence”

We see in the table above that citation metrics reveal significant differences. While 73% of DACH “artificial intelligence” papers are cited, only 39% of DACH “künstliche Intelligenz” publications achieve at least one citation (Table 1). Mean citation counts amplify this disparity: 21.6 citations for “artificial intelligence” papers versus 1.7 for “künstliche Intelligenz” papers.

Can we say more about the citing publications? A deeper dive into disciplines that cite our “KI” and “AI” publications exposes divergent trends. I analysed the resulting datasets from above in the Dimensions “Landscape and Discovery dashboard” on the pattern of citing disciplines - see Figure 2a (“künstliche Intelligenz”) and 2b (“artificial intelligence”).

Both “artificial intelligence” and “künstliche Intelligenz” are predominantly cited by Fields of Research (FoR) for ‘Information and Computing Sciences’ and ‘Engineering’ disciplines. However, the dominance of these fields in “künstliche Intelligenz” citations has eroded in both instances since 2018 (due to “AI” research being cited in different fields and applications). However, for the German “KI” citation base, the two dominant FoRs ( ‘Information and Computing Sciences’ and ‘Engineering’ ) dropped from 90% overall (until 2018) to 50% giving way to citations from ‘Commerce, Management, and Services’ for second place.

Meanwhile, Biomedical and Social Science citations have risen sharply for “KI” publications, potentially signalling a shift toward application-oriented or interdisciplinary research. In contrast, in the case of “artificial intelligence”, citations maintain a steady focus on the FoR based on ‘Information and Computing Sciences’ and ‘Engineering’ with the latter displaying a strong and stable citation share of around 25% over time (cf FoR Engineering citations for “künstliche Intelligenz” drop from 29% in 2018 to 14% in both 2023 and 2024).

Analysis of German “KI”, German “AI”, and Global “AI” Research and Non-Research Outputs

Are other forces at play that can highlight the difference in citation patterns? Dimensions allows for the analysis of different document types and I looked into the distribution of different document types for “KI” and “AI” publications. The different category types can be categorised into research-focused document types including research articles, conference papers, or reviews, and non-Research document types e.g., editorials, book reviews, or errata. Table 2 displays for “KI” and “AI” the citation figures based on the distinction in research versus non-research outputs for DACH publications featuring “KI” and “AI”, respectively. In addition, relevant overall statistics are compiled for global “AI” publications distinguished by research versus non-research document types.

German “künstliche Intelligenz” publications display distinct differences in citation patterns from both German “artificial intelligence” as well as global “AI” publications. Particularly in terms of relative publication volume, and citation impact (see Table 2).

Differences Between German “KI” and German “AI”

German “KI” research is significantly smaller in scale compared to German “AI”, with 3,214 research publications versus 22,673 for German “AI”. Non-research outputs follow a similar trend, although their relative proportion is higher in German “KI” (16.40%) than in German “AI” (8.42%). This significantly higher share of non-research publications may contribute to the comparatively lower citation impact of German “KI”.

Further insights into the citation figures highlight this disparity: German “KI” research has a total of 6,175 citations and a mean citation rate of 1.92, far below the 515,000 citations and a mean rate of 22.71 for German AI. Only 42% of German “KI” research publications are cited, compared to 76% of German AI research outputs, emphasising the limited reach and influence of German KI research in comparison.

How German “KI” Differs from Global “AI”

When viewed against global “AI” trends, German “KI” demonstrates even greater challenges. Its total citations (6,175) represent a minute fraction of the 5.17 million citations attributed to global “AI” research. The mean citation rate for German “KI” research (1.92) is also substantially below the global average of 13.19. A similar trend is observed for non-research publications, with German “KI” non-research outputs achieving a mean citation rate of 0.32 compared to 5.96 globally.

The share of cited research further underscores these differences: only 42% of German “KI” research publications are cited, compared to 60% for global AI research. These figures suggest that German “KI” research struggles to gain visibility and recognition, both domestically and internationally.

In a recent analysis of English as the lingua franca in science we looked at the shares of major languages in the research outputs in Dimensions. The proportion of German publications overall (in the Dimensions database-wide context) is 4%. German “KI” share on a global AI scale is 0.8% of global publications on “AI” - another factor of the diminished relevance of German “KI” publications in a global context (NB: The 22,673 German “AI” publications yield a share of 5.8% for global “AI” publications, see table 2).

The low overall number and this disparity suggest that German researchers rarely publish research on “AI” in German, favouring English for broader reach and impact of their research related to “AI”. This highlights why “künstliche Intelligenz” publications may struggle to achieve similar prominence.

Role of Non-Research Publications in Lowering Citation Metrics

One key factor in German KI’s lower citation impact is the high proportion of non-research outputs (16.40%). These outputs, such as application-focused or teaching-relevant publications, tend to attract fewer citations. The mean citation rate for German “KI” non-research outputs (0.32) is significantly lower than that for German “AI” (10.88) or global “AI” non-research publications (5.96), pointing to potential issues with dissemination, relevance, or impact in these outputs.

Alignment of German “AI” with Global “AI”

In contrast to German “KI”, German “AI” research aligns closely with global “AI” trends in terms of citation dynamics and visibility. The mean citation rate for German “AI” research (22.71) surpasses the global “AI” average (13.19), demonstrating strong impact and integration into the international research community. Additionally, 76% of German “AI” research outputs are cited, exceeding the global average of 60%, further highlighting the recognition and influence of German “AI” research on a global scale.

What Does the Data Tell Us About “Künstliche Intelligenz” Research, and Its Reach?

Challenge of Publishing with “Künstliche Intelligenz”

The German “KI” publications face significant challenges in achieving the same level of visibility and impact as German “AI” ones based on the observations about output numbers and the citation analysis.

Compared to the German “AI” research, the “KI” publications are represented in a different pattern than the comparator groups when looking at the type of publications. Splitting into research and non-research type publications, the difference in citation statistics can be attributed to a higher proportion of non-research outputs and a lower citation share for its research publications.

DACH-based research publishing with “AI“ performs much more comparably to global “AI” and is aligned accordingly. With higher citation rates and a greater share of cited outputs, this is due to adhering to English as the global lingua franca. This also indicates a strong integration of DACH publications that use “artificial Intelligence” into the global research landscape. Further analysis beyond this initial analysis presented here is warranted to elucidate and compare collaboration patterns.

What Are the Reasons for the Differences in “Künstliche Intelligenz” Citation Patterns and Behaviour?

One potential reason for lower citation rates, based on the higher non-research type outputs, may be a focus on applications over academic research: German “KI” non-research outputs might focus heavily on practical or applied aspects of AI for specific industries, such as manufacturing, robotics, or automation. These outputs, while valuable for practitioners, are less likely to be cited in academic literature in the fields of AI, as their primary audience is non-academic. The citation pattern by discipline (see Figure 2a and Figure 2b) may be indicative of that non-academic core discipline-specific citation behaviour.

If not focused on basic research, the emphasis may be on teaching and education: German “KI” non-research publications could include textbooks, teaching aids, or publications aimed at educators, students or the general public. These resources are critical for capacity building but rarely receive citations in research-oriented academic journals and coincide with the fact of the well-embedded use of “KI” by the German public. Particularly the non-research outputs might predominantly be published in German to cater to local & national audiences, limiting their accessibility beyond (language) borders and citation by the global academic community, where English is the primary language.

The language barrier for non-English-type outputs may be a contributing factor to the lower citation rate in particular. This may well be due to the limited visibility in a number of scholarly databases (e.g. Scopus and Web of Science) where non-research outputs, that are indexed in Dimensions, may not be indexed or available at all. Dimensions has a higher share of non-English language outputs than other databases as shown by a large-scale comparison of bibliographic data sources (Visser et al., 2020).

With the citation by discipline analysis above, the limited visibility of “KI” research might also be due to the interdisciplinary status of the “KI”-mentioning research, straddling areas like cognitive science or linguistics, which might fragment citations across fields. If German “KI” research is in these early stages compared to the broader “AI” field, it may not yet have reached the critical mass of high-impact publications needed to attract widespread citations. However, an emerging status of “KI” as a Field of its own can be ruled out: Trend & growth pattern of the number of publications is very similar to the global AI trend and doesn’t warrant a different pattern.

Is “KI” a Niche Research Topic and is it only of local Relevance to DACH Countries?

Research outputs featuring “künstliche Intelligenz” cater to a specific, language-oriented use case on AI research for the native German tongue needs, mostly in outreach, teaching, and education. Relevance to basic research, based on the scientometric data, is very limited on a global scale, so describing it as a niche is true for the language but not in a scientific context. Its prime purpose is to serve dedicated German language dissemination and communication needs. Particularly communication seems key here, literally and figuratively, by translating AI into a German language context. The great thing about finding AI research articles in German is that they can effectively communicate the latest research on AI to non-researchers and non-English speakers. One may argue that this is a clear sign that the German public and industry are to benefit from artificial intelligence research more than other countries, where such prominence of AI in the native language is far less pronounced. While a direct comparison might be unnecessary, this linguistic accessibility demonstrates that the scientific community in Germany is able to bridge cutting-edge science and practical application through effective communication.

This brief exploration opens the door for further investigation. A closer look at institutional affiliations, linguistic preferences, collaboration, funding, and the evolving thematic focus of “KI” versus “AI” research could provide richer insights and shed light on how language — exemplified by examples highlighted here in this analysis — shapes the perception and impact of science in a globalised world.