A ballad of first names; on variants, visibility, and researcher trajectories

Research data bite 22.

Continuing on our name thread, where I previously mused on the geography of a selection of first names in UK research or the variation of surnames across the world, but the picture would not be complete without considering first name variants. In many cultures, people often have an “official” name for formal documents and a “daily life” name, which is often, but not always, a shortened version. So Thomas becomes Tom, Frederik becomes Fred, Christopher becomes Chris, Kathryn becomes Kate, and so on. Most of these are relatively obvious, but there are less familiar cases: in Poland, Aleksandra often becomes Ola; in Spanish-speaking countries, Ignacio becomes Nacho.

I recently curated researchers for a large funder, who had recorded first and last names of awardees as they were provided to them. It was striking how often researchers used their official name when applying for a grant, even though they already published using their usual name (although they may switch back and forth across their career). More surprisingly, a few did the opposite, and published under their official name but applied for grants under a more familiar version. Some intentionally publish under different names altogether, but that is intentional.

Without widespread adoption of ORCID, it often takes a leap of faith to determine that Douglas Adams, who received a grant, is the same person as Doug Adams who published several papers. If they are both at the University of Maximegalon, that leap is smaller; smaller still if they share the same field of research. But the consequences of misattributing smaller researcher profiles are typically lower than those of larger ones, so it makes sense to be cautious. Still, when studying researcher trajectories, we need a way to identify all profiles that belong to the same individual, so here is my attempt at doing so.

Variants in the ORCID dataset

Looking for authoritative sources of first name variants, I stumbled across various lists online [github + project], but most had too many options and focused only on English names, overlooking other languages. I remembered ORCID includes a ‘variant’ field to indicate other names a researcher is known by. I had assumed it would mostly be used for surname changes, but it turns out many researchers use it to record alternative first names—and more unexpected entries like “researcher”, “lecturer”, or even “physician.” Some of the lesser-known pairings I already knew of (Aleksandra/Ola, Ignacio/Nacho, Gopalakrishnan/Gopal) were indeed present in the data, which was reassuring. I even found transliterations from non-Latin scripts—李鹏 listed as a variant of Peng, and 刘锐 as Rui.

At the end of this bite, you will find the GBQ code I used to extract the list (it is part of the free data so anyone with a GoogleCloud should have access, I introduced it here), but I have also added my list in figshare (here). The field is manually filled, so I kept a threshold of minimum two profiles. Proceed with cautious, obviously, as even with a minimum of two researchers, Christopher’s variant was listed as James, likely due to actual name changes rather than variants.

In Dimensions

When curating my list of researchers who had received a grant from a specific funder, I searched for their profiles in Dimensions’ researchers dataset. I incorporated potential name variants from ORCID, and then checked whether:

the publication profile(s) included outputs funded by that funder

the potential matches shared co-authors or research organisations—especially when there were known co-grantees

they published in the expected fields of research

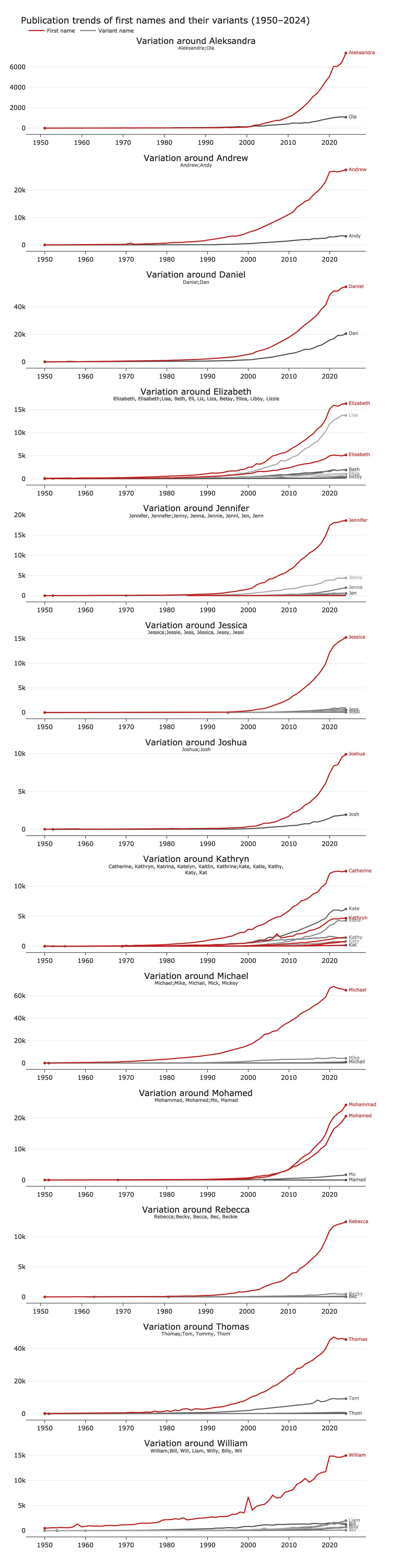

And now, for a bit of visualisation: here is trend for a select list of names and their variants. The bump from 2020–2021 COVID-era publications is clearly visible (affecting, it seems, more men than women), and in most cases, official names remain more common than their casual counterparts.

Conclusion

When working with researcher data in Dimensions and considering career trajectory or checking whether a cohort of funded researchers has published, it is important to keep name variation in mind. A query using only Aleksandra may return their grant record but miss their publishing activity under Ola. ORCID helps close that gap, but until adoption is universal and the metadata consistently filled, ad-hoc projects like this one require a mix of digging, curation, and a healthy dose of skepticism.

Code

to extract the list of variants. This will retrieve some non-relevant pairs, so you can curate the lesser used variations.

WITH name_variant AS (-- Query to map ORCID given names to their variant names

SELECT

TRIM(LOWER(pname.given_names)) AS first_name,

TRIM(LOWER(variant.content)) AS variant_name,

COUNT(DISTINCT s.orcid_identifier.path) AS researcher_count

FROM

`ds-open-datasets.orcid.summaries_2024` AS s,

UNNEST(s.person.other_names.names) AS variant

JOIN

UNNEST([s.person.name]) AS pname

WHERE

pname.given_names IS NOT NULL

AND variant.content IS NOT NULL

AND pname.given_names != variant.content

GROUP BY

first_name, variant_name

ORDER BY

researcher_count DESC)

SELECT * FROM name_variant

WHERE researcher_count > 1